Rather than waiting, Kerr and Thatcher wrote a further batch of songs, including the glammy title track, that altered their whole approach, pushing them towards a sound that didn’t reflect the world outside their studio walls. The pandemic drove a train through the middle of the process, with the first lockdown hitting midway through recording. It’s a juxtaposition that really gave me new life to continue writing songs in this way, because it wasn’t as weird as it sounded on paper.” But, lyrically, all I wanted to talk about was where I’d just come from. So when I was making music I just had this energy and I wanted to reflect how I was feeling. “I’d just come out of quite a dark spot in my life, and I felt fucking amazing every day. “I think it came from how I was feeling,” he says. Typhoons is the work of a sober musician who wants to celebrate a change in circumstances, but also a musician who’s only really about writing what he knows. Eventually, he was rocked by how easy it was to function while drinking as heavily as they were. He struggled with depression while making How Did We Get So Dark? and as those songs moved from studio to stage he slipped into the often hedonistic mechanics of being a touring musician. It’s your classic Abba-style collection that hides some crushing lows amid songs that outwardly implore you to lighten up and follow your hips to the dancefloor. Kerr’s state of mind when writing also played a major role in how Typhoons shaped up.

So the bass sounds I was making really informed a lot of the parts.” When you have loads of pedals on it changes the way you play, you know? In the same way, when you try a new pedal you react to what that pedal is doing, and it almost informs your playing a little bit. I feel like a bass player on this album,” he says. Is his relationship with Thatcher more like a traditional rhythm section than it has been in the past? Kerr still has a stack of boisterous riffs to hand but his playing is more empathetic, underpinning string stabs and playful keys. Boilermaker, all skronk and golden age percussion, and Trouble’s Coming, as close to Royal Blood-goes-disco as we’ll ever get, were the first cabs off the rank. This shift in priorities was signalled early on. Obviously it’s processed, but it felt more true to how Joe Bloggs knows what a bass is.” It felt a little bit more pure in terms of a bass sound. I will say, though, that even the 75 per cent of the core sound had shifted a bit, in that it was a much more bass-driven sound rather than loads of pedals and octaves. Once we got that, it was about carefully injecting new sounds around what we were already doing. “It was almost like that was 75 per cent of the content, so it was about the ratio of old with new and getting that balance right. “We just made sure that the core of the music was bass, drums and my vocals,” he adds. “It’s drastic in its own context but ultimately we feel these songs are going to be friends,” Kerr says when asked how the new material might sit alongside old favourites live. Gone is that muscular, fuzz-fuelled stomp, with pastel-hued pop-rock and synth flourishes inspired by Daft Punk, Justice and the production of the late Cassius co-founder Philippe Zdar in its place. It recently became their third number one in the UK – following up their self-titled bow and 2017’s difficult second album How Did We Get So Dark? -but it crested that peak by doing something different. Royal Blood’s new album Typhoons situates Kerr’s bullish, riff-based playing in fresh surroundings. But they find things that I haven’t discovered. I’ve seen videos of people going and emulating my sound, and they do it so wrong. And there’s a bit of fun in not telling someone.

Over time, I’ve realised that, actually, you can’t just walk out with that bass sound. I gave so much of the credit away to the sound. “But at the beginning, I had impostor syndrome. “I was so excited when I discovered this sound,” he admits.

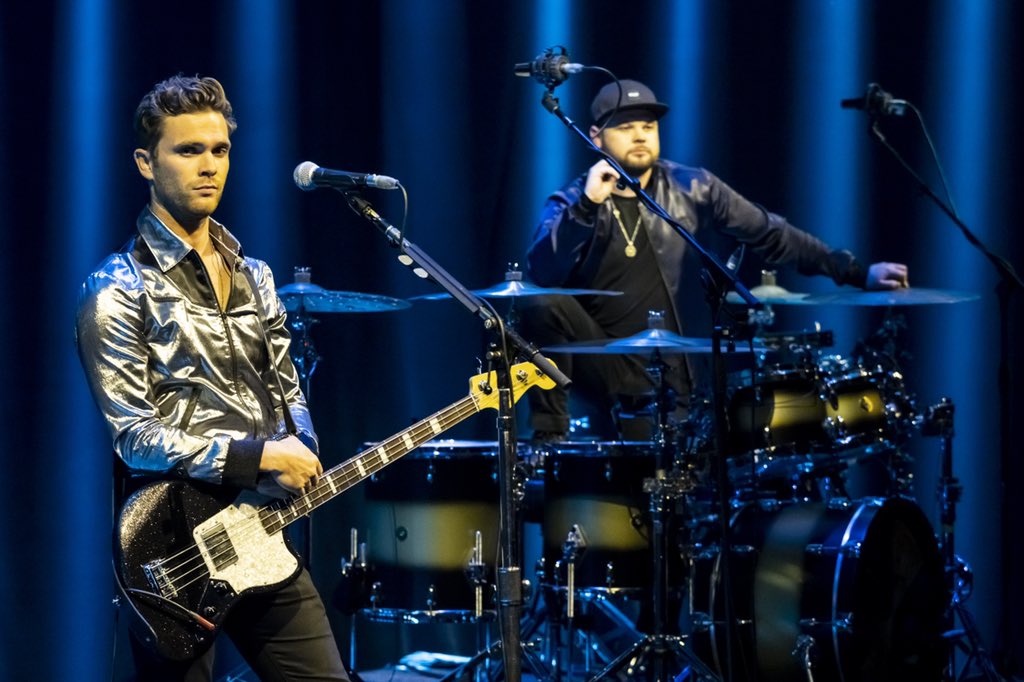

There have been two-piece rock bands before, and there will be many more in the future, but few have been so concise in their desire to shake fillings loose. If you’re aware of Royal Blood, then you’re also aware of the sound - the crushingly heavy, obscenely loud noise that rolls from Mike Kerr’s bass, striding forward in tandem with Ben Thatcher’s thunderous drumming.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)